Scientists found the newly discovered single-celled archaea living in hot spring sediments

Earth’s hot springs and hydrothermal vents are home to a previously unidentified group of archaea. And, unlike similar tiny, single-celled organisms that live deep in sediments and munch on decaying plant matter, these archaea don’t produce the climate-warming gas methane, researchers report April 23 in Nature Communications.

“Microorganisms are the most diverse and abundant form of life on Earth, and we just know 1 percent of them,” says Valerie De Anda, an environmental microbiologist at the University of Texas at Austin. “Our information is biased toward the organisms that affect humans. But there are a lot of organisms that drive the main chemical cycles on Earth that we just don’t know.”

Archaea are a particularly mysterious group (SN: 2/14/20). It wasn’t until the late 1970s that they were recognized as a third domain of life, distinct from bacteria and eukaryotes (which include everything else, from fungi to animals to plants).

For many years, archaea were thought to exist only in the most extreme environments on Earth, such as hot springs.

But archaea are actually everywhere, and these microbes can play a big role in how carbon and nitrogen cycle between Earth’s land, oceans and atmosphere.

One group of archaea, Thaumarchaeota, are the most abundant microbes in the ocean, De Anda says (SN: 11/28/17). And methane-producing archaea in cows’ stomachs cause the animals to burp large amounts of the gas into the atmosphere (SN: 11/18/15)

Now, De Anda and her colleagues have identified an entirely new phylum — a large branch of related organisms on the tree of life — of archaea.

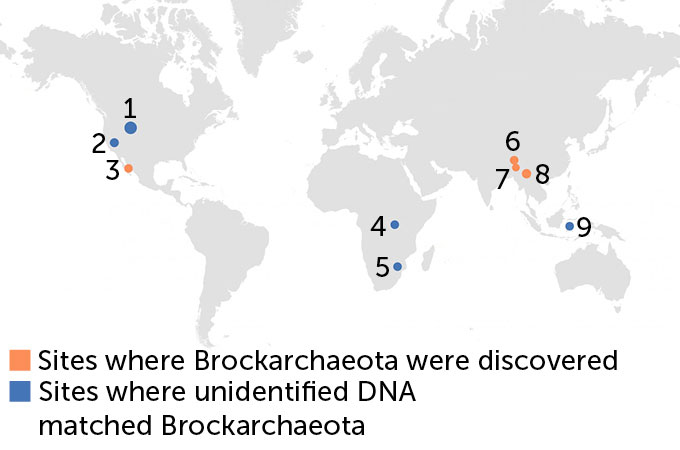

The first evidence of these new organisms were within sediments from seven hot springs in China as well as from the deep-sea hydrothermal vents in the Guaymas Basin in the Gulf of California.

Within these sediments, the team found bits of DNA that it meticulously assembled into the genetic blueprints, or genomes, of 15 different archaea.

The researchers then compared the genetic information of the genomes with that of thousands of previously identified genomes of microbes described in publicly available databases. But “these sequences were completely different from anything that we know,” De Anda says.

She and her colleagues gave the new group the name Brockarchaeota, for Thomas Brock, a microbiologist who was the first to grow archaea in the laboratory and who died in April. Brock’s discovery paved the way for polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, a Nobel Prize–winning technique used to copy small bits of DNA, and currently used in tests for COVID-19 (SN: 3/6/20).

Brockarchaeota, it turns out, actually live all over the world — but until now, they were overlooked, undescribed and unnamed.

Within the new genomes, the team also hunted for genes related to the microbes’

Once De Anda and her team had pieced together the new genomes and then hunted for them in public databases, they discovered that bits of these previously unknown organisms had been found in hot springs, geothermal and hydrothermal vent sediments from South Africa to Indonesia to Rwanda.